The difference between penny-pinching and true low-cost strategies

Happy New Year to my readers! I know it’s been a while; I took a short break from writing during the holidays (and after getting a bad case of Covid), but I am excited to be back with more content.

Over the last few weeks of 2021, I wrote about economies of scale and discussed ways for businesses to improve their bottom line. Of course, every company wants to lower their costs to either improve their profits, pass savings onto their customers to gain market share, or for other reasons. But some companies are going further and excel at reducing costs: these are the successful adopters of low-cost strategies.

Introduction

Sure, economies of scale can help companies generate more profit, allowing them to be slightly more cost-competitive. For the most part, these changes do not require tremendous changes to the company’s offer and business models. However, for those offering a true low-cost strategy, small savings passed onto the customers are not enough. The champions of low prices are doing more than just penny-pinching. We all like to save money, and I wouldn’t pay attention to a company offering me to save a few pennies if their competitor is slashing their prices. I love my IKEA furniture, and I don’t mind assembling them myself if I can save tens or even hundreds of dollars. But would I do it to save $2 or $3?Probably not.

So how can companies successfully compete on price and become serious contenders strong enough to challenge their established but more expensive competitors? What are the strategies used by Aldi, IKEA, or Southwest airlines that disrupt entire industries? In this article, I want to highlight some of the ways these companies shape their offers and business models.

A difference in their value proposition

As you can see from the examples above, these companies are extremely aggressive in their marketing messages. While the traditional players might engage in price wars and cut prices, the successful low-cost companies are able to offer unmatchable low prices and still be profitable. The difference in price is large enough that customers will notice, and some will flock to the low-cost offers.

A prime way to achieve such a huge difference in price is arguably to save on what is unnecessary, whether it is product features, additional services, or steps in processes. Taking things away from the customer sounds like a bad thing, but many customers are willing to make the trade-off if they can get significantly better prices. A good way to put it on paper is to use the value curve analysis framework (https://www.blueoceanstrategy.com/tools/strategy-canvas/ – I recommend the excellent Blue Ocean Strategy book, by Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne).

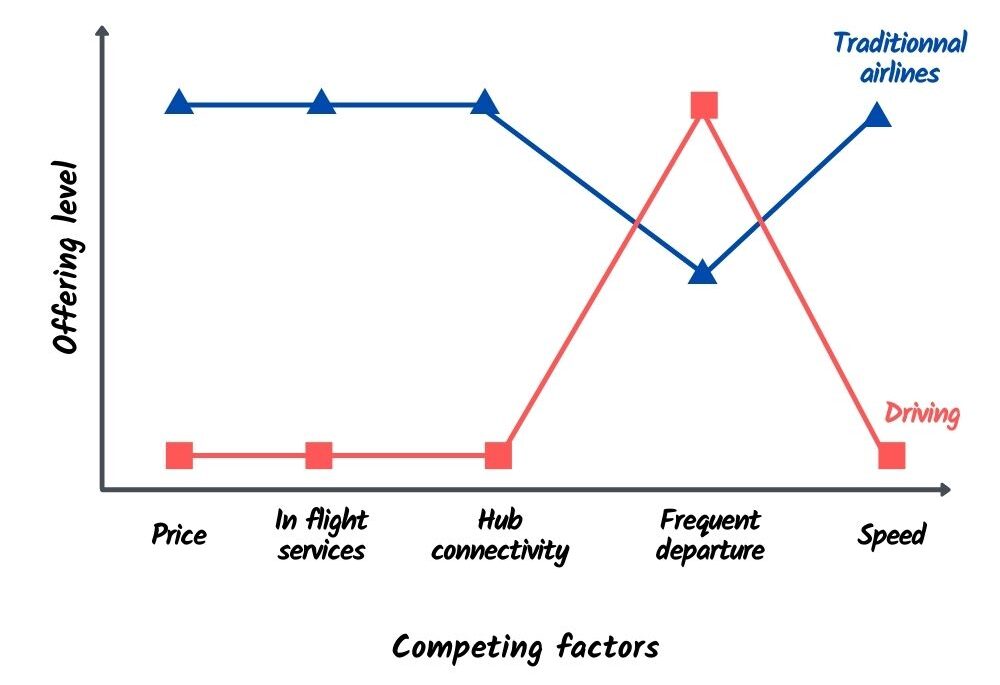

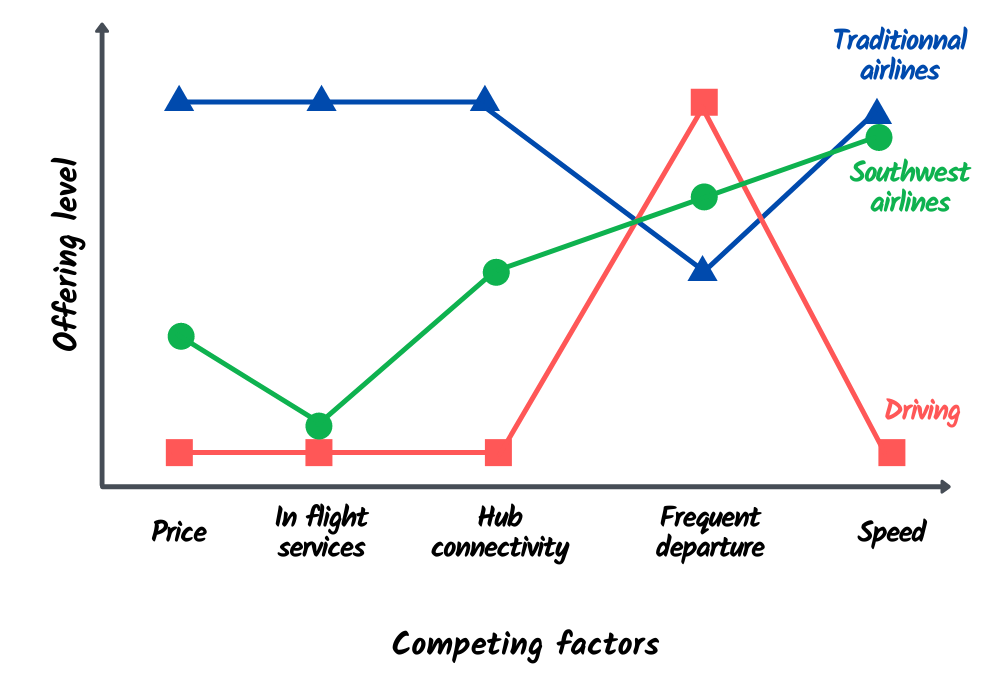

Let’s use the airline industry as an example. Back in the day, the main options to travel long distances were to drive or fly via a traditional airline. Driving is cheap; you can leave your home whenever you want, but it is slow and there are no in-car services. Flying is a lot more expensive and requires more planning, but it is also a lot faster, and in-flight meals and entertainment are available. The value curve framework compares multiple options based on several competing factors (horizontal axis) on their offering levels (vertical axis).

Years ago, there was no in-between: customers who wanted to fly had to pay a hefty price to cover the cost of fuel and employees’ wages, but also the services offered by airlines. Low-cost airlines realized that many customers don’t actually care about in-flight services, fancy meals, and the ability to fly to and from many airports. They took away features that price-conscious customers thought were unnecessary, which helped them come up with much lower prices. Combined with extremely efficient operations (for example, many low-cost airlines are only using one type of plane, which makes maintenance a lot easier and cheaper), and companies like Southwest are now some of the most successful airlines in the world.

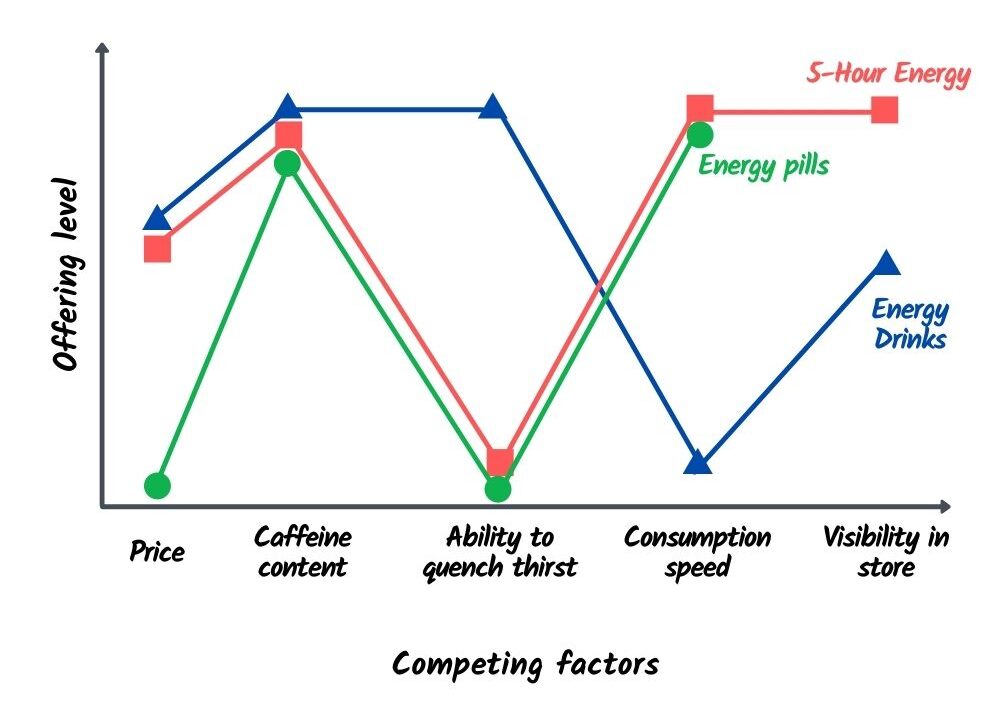

A more personal example for me is the energy pills market. When I started my first business, energy pills were not popular in France. These were, however, a great alternative to energy drinks for some customers. Those looking for a high dose of caffeine who don’t care about hydrating (having to drink 8 to 16oz can be annoying for customers who don’t like the taste of energy drinks) could use a pill. Not having to dilute the caffeine in liquid and flavoring and the reduction in size makes the energy pills several times cheaper than drinks. It is also very convenient: a bottle of 30 pills fits in any purse, backpack, or car. Although I was not competing directly with energy drinks by offering a low-cost drink, I was offering a much cheaper alternative to customers in search of a cheap caffeine fix.

Innovative and optimized processes

A segment of customers will shop based on price and will be willing to make concessions in order to get the best prices. They will be less loyal to brands and will buy from a competitor if their prices are better. The low-cost champions make it very difficult for their traditional competitors to compete on price, and traditional companies are not always successful at launching their own low-cost operations.

Aldi can offer its customers lower prices, due to its unique setup. Their assortment is much smaller than traditional supermarkets: less than a thousand products, versus tens of thousands for the large supermarket chains. They are saving on their supply chain operations and are able to order larger volumes and negotiate better prices. This makes traditional supermarkets struggle to compete on price due to their larger assortments.

They also have several tactics to save time and money within their stores. For example, customers have to bring their own bags or buy some from Aldi. Most products are still on pallets and not nicely displayed on shelves, which saves employees’ time. Customers have to bag their own groceries, which can be shocking to first-time customers but saves the employees so much time that the company does not need as many cashiers as a traditional store. It feels weird to have an employee almost throw your groceries at you, but you quickly forget about that inconvenience once you look at the amount on your receipt. All these tactics allow the company to offer lower prices than its many competitors, without compromising on quality: most Aldi products rank highly in taste tests, and the customers’ satisfaction rates are also high.

Innovation often plays a huge role in the rise of cost leaders. We talked about Aldi’s in-store tactics, and I mentioned in previous blog posts Henry Ford’s assembly line, which decreased the cost of the Model T from $850 in 1908 to $310 by 1926. We can also talk about IKEA and their “flat packing” method of selling furniture in pieces that the customers have to assemble themselves. IKEA saves on assembly, transportation, and storage costs, and customers can enjoy stylish furniture at a low cost. The idea of letting the customer assemble their own furniture seems basic these days, but someone had to think about it first. Now, IKEA is a giant that serves close to a billion customers worldwide, with revenues exceeding $40B per year.

Conclusion

The leaders of low-cost products and services are doing more than just penny-pinching and super-efficient operations. They use a widely different business model and tailor their offer to meet the needs of price-conscious customers. Sometimes, the idea of saving a lot of money beats some unnecessary features that are “standard” in the industry.